Trauma Is Less About the Event, More About the Adaptation

In clinical practice, a recurring observation stands out: many individuals who live with chronic anxiety also report two things—they experienced trauma in childhood, and they cannot recall much from those early years. This overlap raises important questions about the relationship between trauma, memory, and anxiety.

Drawing on insights from developmental psychology, neuroscience, and medicine, as well as my own personal history of limited childhood recall, I want to explore why these patterns emerge. Some of this remains speculative, but it is speculation grounded in years of patient experiences and in the neurobiology of how the human mind adapts under stress.

Trauma Is Less About the Event, More About the Adaptation

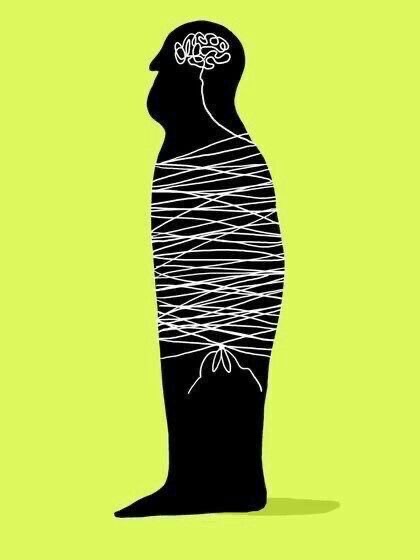

When people hear the word trauma, they often assume it refers to the specific event—a frightening incident, abuse, or neglect. But trauma is better understood as the way the mind and body respond to those experiences.

In this sense, trauma is not the event itself. Trauma is the accommodation—the adaptations your nervous system makes to keep you safe in the face of overwhelming threat. These adaptations, while protective in childhood, often persist into adulthood, where they can create significant challenges.

The Nervous System’s Protective Strategies

It is crucial to recognize that what looks like dysfunction is often the nervous system’s best attempt at protection. Patients often feel relief when they realize their responses are not signs of being “broken,” but evidence of resilience.

Take compulsive worrying as an example. If a child grows up in an unpredictable environment where they have little control, the brain learns a survival strategy: constant vigilance. The mind warns of every possible danger, hoping to prevent harm. While this adaptation is protective in childhood, it can evolve into chronic anxiety later in life. In essence, the protective stance becomes the source of ongoing distress.

Memory Gaps Do Not Always Signal Trauma

Another common theme is poor recall of early life. Many people with trauma say they remember very little of their childhood. Understandably, this can cause concern—does forgetting mean something terrible must have happened?

The answer is more nuanced. While memory gaps can sometimes be linked to trauma, they do not automatically indicate it. Human memory exists along a continuum. Some individuals have exceptional recall; others naturally remember less. Limited memory, on its own, is not proof of traumatic experience.

What truly matters is not how much one remembers, but whether present patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior reflect unresolved distress.

A Shift in Perspective

Healing often begins with reframing. When patients come to see their anxiety or memory difficulties as survival adaptations rather than flaws, an important weight of shame is lifted. Their nervous system was not broken—it was adaptive.

Understanding trauma as an accommodation of the nervous system allows us to respect those protective mechanisms while also working toward healthier ways of responding in the present.

Conclusion

Chronic anxiety and gaps in childhood memory often intersect with trauma, but the relationship is complex. Trauma is less about what happened and more about how the nervous system adapted. Those adaptations, though protective in childhood, may create difficulties later.

Recognizing anxiety as a survival strategy—rather than a personal weakness—can transform the healing process. It reframes symptoms as evidence of resilience and opens the door to growth, self-compassion, and recovery.

Comments (0)